Travelling the world (1925-1933)

October 1925 marked the beginning of a lengthy period in which Kazantzakis travelled the globe. On every journey he gathered images, ideas and experiences which he incorporated into the subsequent reworking of the Odyssey.

By 1933 he had visited the Soviet Union and Spain three times. He also travelled to Italy, Cyprus, Palestine, Egypt and the Sinai Desert, and stayed for extended periods at Gottesgab in Czechoslovakia.

His travels and intensive work helped him to endure the death of his parents in 1932. He worked at a feverish pace, writing film scripts and poetry, composing plays and drawing up novels in French, compiling encyclopaedias, dictionaries and schoolbooks, contributing to Greek and Russian newspapers and translating major works of literature as well as children’s books.

Kazantzakis planned political and literary activism with the Greek-Romanian author Panait Istrati, in whom he believed he had found yet another spiritual companion. Lastly, his meeting with Prevelakis was to grant him a faithful friend and dedicated disciple.

Journeys

Kazantzakis notes that travel and the creative process were the two greatest joys in his life. Though he often travelled as a newspaper correspondent, earning a living was never his motive – work as a correspondent allowed him to satisfy his wanderlust.

Travel itself was a process which, in showing him different places and people, led him to self-knowledge, the transcendence of egotism and the adoption of an all-embracing perspective. He went everywhere and saw everything in the countries he visited: cities, villages, the countryside, museums, important public figures and ordinary people.

His ability to tune in to the distinct, often hidden soul of a place is exquisitely recorded in the pages of his travel books, which are regarded as the epitome of Greek travel writing.

Images, Ideas and Experiences

Kazantzakis’ letters to Prevelakis clearly record how impressions from his travels were used to enrich the Odyssey.

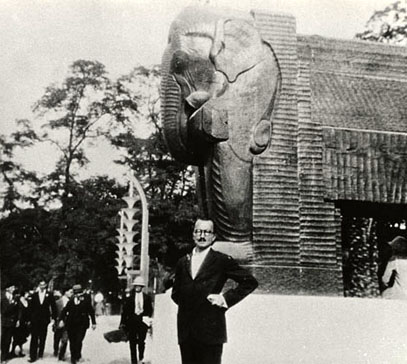

It is also well known that in the summer of 1931 Kazantzakis went to Paris to see the Colonial Exhibition in the Bois de Vincennes. As was customary, the organisers had transported entire villages from every colony, together with their inhabitants. Visitors could see the natives living their everyday lives and attend “live” spectacles such as battles and ritual dances.

Kazantzakis used these images to recreate the primitive world in his Odyssey.

The Soviet Union

Kazantzakis first visited the Soviet Union from October 1925 to January 1926, as a newspaper correspondent for Eleftheros Logos [Free Speech].

On his second journey he was a guest of the Soviet Government for the tenth anniversary of the Revolution, staying from October to December 1927. It was then that he met Itka Horowitz, a friend from his Berlin days, and made the acquaintance of the Greek-Romanian author Panait Istrati.

On his third journey (from April 1928 to April 1929) he contemplated settling permanently. Having met up with Istrati in Kiev, he went with him to live in Bekovo and then travelled to various parts of the country.

In Bekovo Kazantzakis lived with Itka for a while, and in August 1928 went to meet Eleni. Initially in the company of his friends and later alone, he toured the Caucasus, South Russia and part of Siberia.

These travels provided the inspiration for his novel Toda Raba.

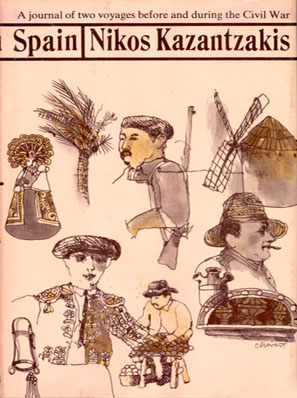

In Spain

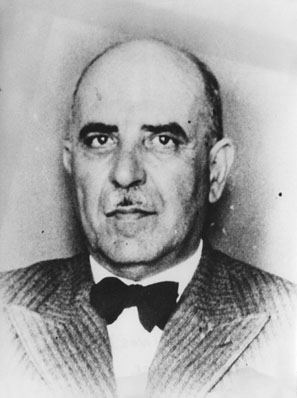

In late summer 1926 Kazantzakis spent a month travelling in Spain as a newspaper correspondent for Eleftheros Logos [Free Speech], and interviewed General Primo de Rivera, the Spanish dictator.

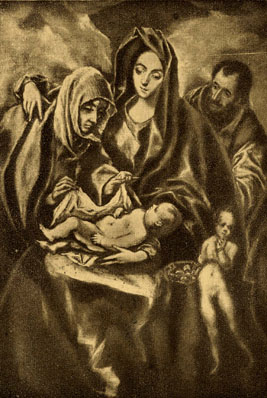

On his next journey, from October 1932 to December 1933, he spent an extended period in Madrid studying Spanish literature. Following his father’s death he toured the country by train. Key moments on this journey were his visit to Toledo and encounter with the art of El Greco.

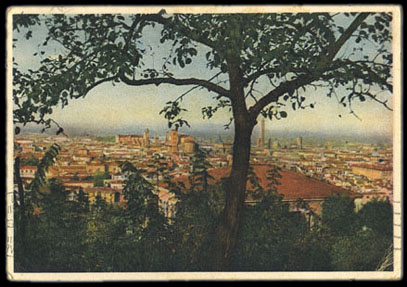

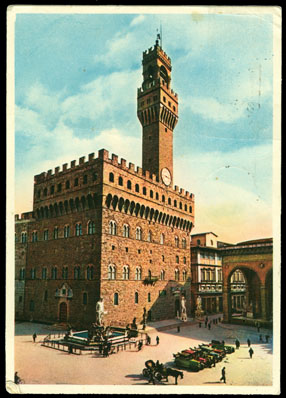

Italy

Italy was one of Kazantzakis’ favourite destinations. He had already visited the country twice when, in October 1926, he made a further trip as a newspaper correspondent for Eleftheros Logos [Free Speech]. He interviewed Mussolini in Rome and, as was only to be expected, did not neglect to pay a short visit to Assisi.

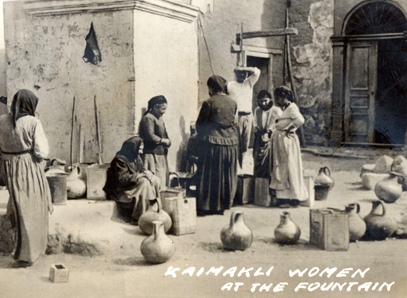

Cyprus

On the way back from Palestine in May 1926, Kazantzakis, Eleni Samiou and the Papaioannou sisters spent a few days touring Cyprus. There the author interviewed Hussein ibn Ali, the exiled King of Hejaz, which later became part of Saudi Arabia. Kazantzakis’ impressions of Cyprus were published in the Eleftheros Typos [Free Press] newspaper.

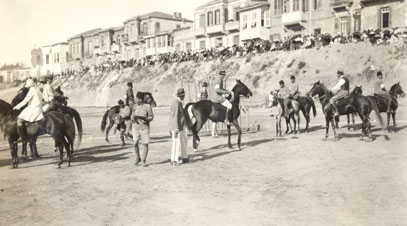

Palestine

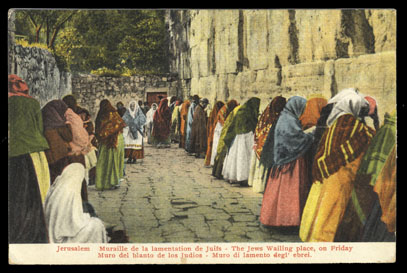

In April and May 1926 Kazantzakis travelled to the Middle East as a newspaper correspondent for Eleftheros Logos [Free Speech], together with Eleni Samiou and the Papaioannou sisters.

In Palestine, where he unexpectedly ran into Elsa Lange and Lea Levin, two friends from Berlin, he was deeply moved by the experience of Easter - an experience which later became part of The Last Temptation. In Jerusalem he was particularly struck by his visit to the Omar Mosque, and by the sight of Christians, Jews and Muslims living together.

Egypt

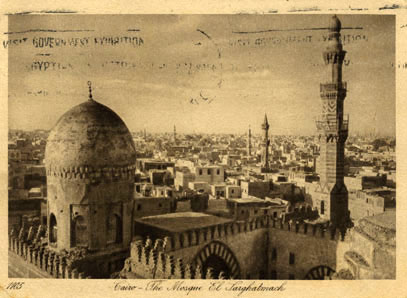

In early 1927 Kazantzakis was back in his favourite place, the East, on a journey to Egypt and Sinai as a newspaper correspondent for Eleftheros Logos [Free Speech].

The mystical holiness of the Nile and the backbreaking struggle of the fellaheen were imprinted on his mind, providing material for his Odyssey. He visited the pyramids and Upper Egypt, Cairo and Alexandria, where he had a seminal meeting with C. P. Cavafy.

Sinai

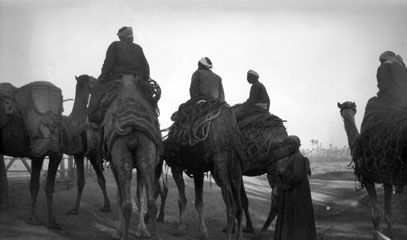

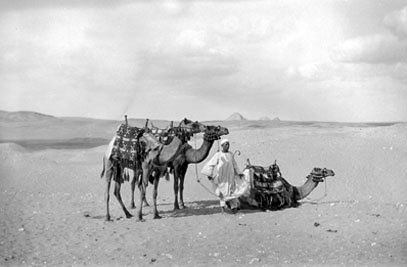

In February 1927 Kazantzakis left Egypt for the Sinai Desert, where he spent about a fortnight. The journey through the desert, the wild landscape and the “God-trodden Mountain” evoked the harsh face of the Old Testament God.

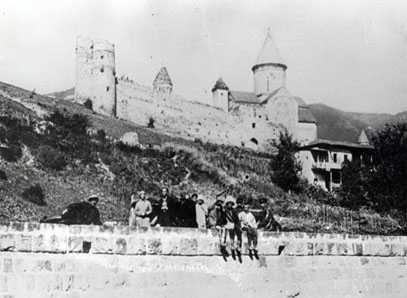

The isolated Monastery of St. Catherine, rising like a fortress in the middle of the desert, was to his eyes yet another symbol of the human struggle.

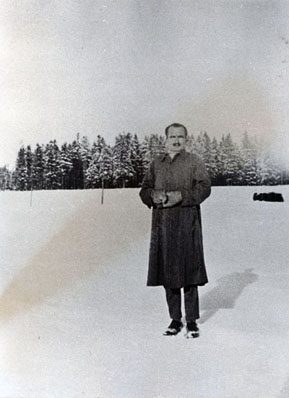

Gottesgab

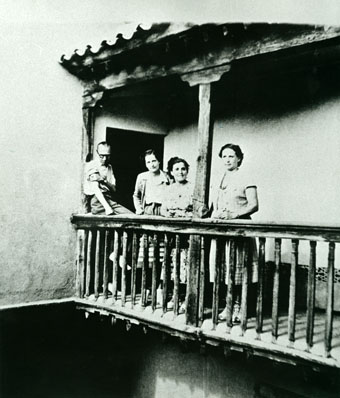

In May 1929, while the Kazantzakis couple were travelling by train from France to Prague, a coal miner told them about an area of Czechoslovakia called Gottesgab. They lived there for a year, in a house “all alone in the forest”.

In June 1931 they returned to Gottesgab and lived in the same house for one more year, at the end of which Prevelakis visited them.

Film scripts

While in the Soviet Union, Kazantzakis kept abreast of cinema output, studied books on the cinema and wrote two scripts which were accepted by Soviet cinema companies (The Red Kerchief and Saint Pachomius and Co.), though it is not known whether these were ever made into films.

He also prepared a further scenario entitled Lenin; the initial idea from this was used in his novel Toda-Raba.

In 1931-2 he turned his attention to European cinema. He adapted Bocaccio’s Decameron and wrote scripts entitled “Don Quixote”, “Buddha”, “Mohammed” and “A Solar Eclipse”, which latter he intended to submit to the competition announced by the League of Nations.

For all the efforts made by Prevelakis, none of the scripts was ever filmed.

Novels in French (1929-1930)

While in Gottesgab from 1929 to 1930, Kazantzakis wrote the novel Toda-Raba under the initial title Moscou a crié [Moscow Cried Out]. He also began the novel Kapétan Élias, which he later made use of in Freedom and Death.

It is interesting that all of these works were written in French; this is a sign that Kazantzakis had decided to break out of the narrow confines of the Greek-language public.

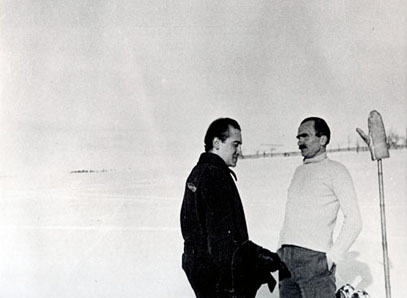

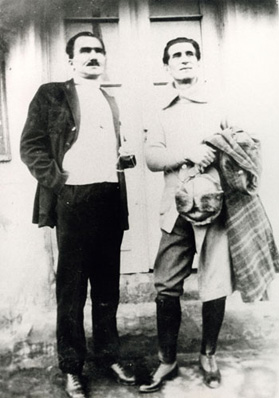

Panait Istrati

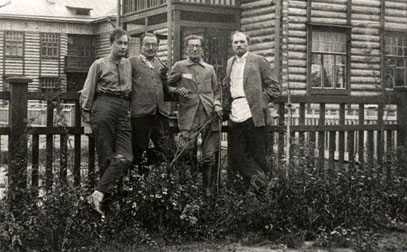

Kazantzakis met Panait Istrati in November 1927, during his second trip to the Soviet Union.

What united the two men was their enthusiasm for social revolution; what separated them was their different worldviews. Although they decided to work together in literature and politics, Kazantzakis could not reconcile himself to his friend’s materialistic outlook, while Istrati found the Cretan’s thought too metaphysical.

In 1928 they arranged to meet up in the Soviet Union, planning a grandiose series of political articles in the global press. Yet their dissimilar characters and other differences led to them heading their separate ways, probably feeling embittered.

Whatever the case may be, they continued to write to each other over the following years, and Kazantzakis dedicated his canto entitled “Don Quixote” to Istrati.

Activism

In January 1928, following a request made by Dimitris Glinos, Kazantzakis and Istrati addressed a public meeting at the Alhambra Theatre in Athens. Istrati’s speech stirred the audience, which went on to hold a rowdy demonstration after the event, provoking the intervention of the police.

Istrati was threatened with deportation, but was eventually placed under house arrest at G. Nazos’ house in Kifissia. Charges were pressed against Kazantzakis and Glinos for fomenting the demonstration, but when the case came to trial a few months later, Glinos stood alone in the dock, since Kazantzakis was in Kiev; the court cleared both men.

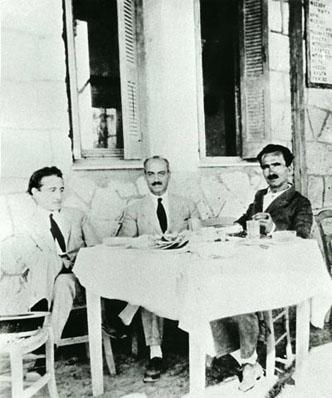

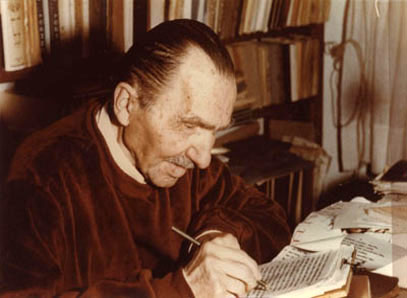

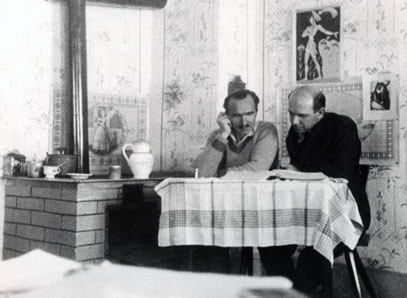

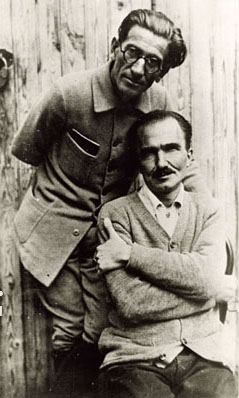

Pantelis Prevelakis

On 12th November 1926, Pantelis Prevelakis met Kazantzakis in Athens, at the house of his sister Eleni Theodossiadi. Prevelakis was only seventeen years old at the time. In him, Kazantzakis was to find an undyingly devoted fraternal friend, who followed both his physical travels around Europe and Greece and his metaphysical quests, and worked with him over many years on assorted writing projects.

Kazantzakis called him “brother”, dedicating Salvatores Dei and the canto “Greco” to him, and presenting him with the manuscript of the Odyssey.

Prevelakis followed Kazantzakis’ work and affairs with incredible devotion: supervising editions of his works in Athens; corresponding with critics and translators; mediating with publishers to get him paid commissions; working systematically for his appointment to UNESCO and on the Nobel Prize nomination.